It has been another interesting day in the world of Aramaic Studies. Hopping around Yahoo Answers, I came across a link to a webpage that had a number of really… ‘interesting’ translations of the Lord’s Prayer from “the original Aramaic.” This gave me so much of a headache that I had to come here and discuss it so that those who are fortunate enough to come across this blog know what to look out for and what not to trust.

The following is only for academic purposes. Let it be known up front I do not endorse these translations by any means as academic or true to any known Aramaic text. With that said… here is what I came across:

Exhibit 1: Spurious

(in the original Aramaic)

“Oh Thou, from whom the breath of life comes,

who fills all realms of sound, light and vibration.

May Your light be experienced in my utmost holiest.

Your Heavenly Domain approaches.

Let Your will come true – in the universe (all that vibrates)

just as on earth (that is material and dense).

Give us wisdom (understanding, assistance) for our daily need,

daf chnân schwoken l’chaijabên.

detach the fetters of faults that bind us, (karma)

like we let go the guilt of others.

Let us not be lost in superficial things (materialism, common temptations),

but let us be freed from that what keeps us off from our true purpose.

From You comes the all-working will, the lively strength to act,

the song that beautifies all and renews itself from age to age.

Sealed in trust, faith and truth.

(I confirm with my entire being)

Exhibit 2: More Spurious

A Translation of “Our Father” directly from Aramaic into English

Exhibit 3: Neil-Douglas Klotz’s “Translation”

Lords Prayer, from the original Aramaic

Translation by Neil Douglas-Klotz in Prayers of the CosmosO Birther! Father- Mother of the CosmosFocus your light within us – make it useful.Create your reign of unity now-through our fiery hearts and willing hands

Exhibit 4: G.J.R. Ouseley’s “Translation”

Translation by G.J.R. Ouseley from The Gospel of the Holy Twelve

The Verdict:

What do all of these “Translations” have in common? They exploit (whether intentionally or unintentionally) the unfortunate fact that the general public knows little to nothing about the language. From a scholarly standpoint, these translations have about as much in common as actual Svenska has to the cute and inane babblings of a certain loveable Muppet.

For the record, let it be known that I have absolutely no problem with mysticism and I find it a valid expression of religion. I do, however, have a problem with mistaken claims, regardless of their source. As such, I find these interpretations particularly upsetting but, if you take a step back, they are understandable from their authors’ points of view.

The point of mysticism (as I’ve come to see it) is to actively seek out direct experience with the divine. As these interpretations are rendered, I believe that we can greatly understand their authors’ religious experience and conceptions of God and the cosmos. However, when working with a language in translation, a translator must try their best to shed their undue biases and attempt to convey a plain meaning of the text in question rather than the meaning that they imply, impose or wish to interpret into.

This truly has made religious texts a can of worms for translators, from ancient times to present as religious texts are what people look into to find inspiration for daily life, help in times of need, a sense of identity, and (most importantly) the divine. There are so many expectations, emotions, and theological implications that things can get clouded, and at many times heated (think of the King James Version Only Movement or the New World Translation).

It’s enough to give you a headache. 🙂

What Does the Prayer Actually Say?

I suppose that it’s the next logical thing to ask. 🙂 Before we can answer that question, however, we first need to ask, “Which ‘Original’ Aramaic Lord’s Prayer are we talking about?”

There are, unfortunately, several Aramaic versions that exist historically. By far the most famous is the one found in the Syriac Peshitta. Generally when someone refers to the “Original Aramaic” they’re talking about this one. A wonderful recording of it was done by SAVAE (the San Antonio Vocal Arts Ensemble) and it can be found here (it’s #3 on the list and rather pretty; also notice that they’ve fallen to the interpretation by Neil Douglas-Klotz as shown above. I’ve contacted them about it over the past number of years since the Ancient Echoes CD came out, but they haven’t done a thing about it after numerous conversations via email… ~sigh~).

Next is the version found in the Old Syriac Gospels (OS), a set of two manuscripts (the Sinaitic Palimpsest and the Curetonian texts) that are written in an older dialect of Syriac than the Peshitta and are generally believed to be what the Peshitta was redacted from at a later date (how much and in what manner is up to debate, but it is generally believed that the Peshitta came from the OS being edited to match the Greek tradition at the time). The Prayer as found in the OS is in a slightly different order and very slightly different wording (even between manuscripts); however, these differences are nothing much more than one would find between two modern Bible translations. They basically say the same thing.

The Translation

Below I’ve included a transliteration of the Lord’s Prayer from the Syriac Peshitta with my own translation and notes. I’ve tried to break things down word by word to clear up any misconceptions, questions or naysaying. This isn’t a perfect translation, as no translation is, but I believe that it does a better job outlining things in a more or less comprehensive fashion:

Notes on transliteration below:

- v = “v” made with both lips

- dh = “th” as in “this”

- kh = “ch” as in “Bach”

- q = a hard “k” in the back of the throat

- th = “th” as in “three”

- sh = “sh” as in “shoe”

- ` = a hard “uh” in the back of the throat

- ‘ = a glottal stop; separate the sounds

- – = just a separation between grammatical structures for understanding. It doesn’t affect pronounciation.

- The vowels are only most-likely examples as they vary greatly between dialects, but will follow the general pattern I’ve outlined.

Abwun dvashmaya

(Our father who is in heaven.)

abwun = our Father

d-va-shmaya = of whom/which – in – heaven

Nethqadash shmakh

(May your name be holy.)

nethqadash = will be holy

shmakh = your name

Note: The imperfect or “future” tense can be used in some cases as an adjuration, i.e. “May so-and-so happen.”

Tethe malkuthakh

(May your kingdom come.)

tethe = it will come

malkuthakh = your kingdom

Nehweh tsevyanakh

(May your will be [done])

nehweh = it will be

tsevyanakh = “your will” or “your desire”

Note: This literally means closest to “Your will will be” which is awkward in English at best.

Aykana dvashmaya

(As it is in heaven)

aykana = like, as

d-va-shmaya = of whom/which – in – heaven

Af bar`a

(Also [be] on the earth)

af = also

b-ar`a = in/on – the earth

Hav lan lakhma

(Give us bread)

hav = give

lan = to us

lakhma = bread

Dsoonqanan yomana

(That we need today)

d-soonqanan = of which – we lack/need

yomana = “today” or “daily”

Ushvuq lan khaubeyn

(And forgive our sins)

u-shvuq = and allow/forgive

lan = unto us

khaybeyn = our sins/debts/shortcommings

Aykana d’af khnan

(Also as we)

aykana = like

d-af = in the same manner – also

khnan = we

Shvaqan lkhaiveyn

(Have forgiven sinners)

shvaqan = we’ve forgiven

l-khaiveyn = unto – sinners/debtors/the guilty, etc.

U’la te`lan lnisyouna

(And don’t lead us into danger.)

u-la = and – not

te`lan = “lead us” or “cause us to enter” (could be either due to verbal form ambiguity)

l-nisyouna = unto – danger/temptation

Ela patsan men bisha

(But deliver us from evil)

ela = but

patsan = deliver us

men = from

bisha = evil

Metul d’dheelakh hee malkootha

(Because the Kingdom is yours.)

metul = because

d-dheelakh = of which – “yours” (it’s a grammatical construct signifying ownership which is a bit complicated to explain here)

hee = is

malkootha = kingdom

Ukhaila utheshbookhtha

(And the power, and the glory)

u-khaila = and – power

u-theshbooktha = and- glory

`Alam l`almeen

(Forever; To eternity)

`alam = forever

l-`almeen = unto – the ages (idiom. “eternity”)

Ameyn

(Amen)

ameyn = “truly” or “it is truth!” traditional ending to prayer or an oath (e.g. “ameyn ameyn amarna lakh” = “truly, truly I’m telling you!” or “I swear!”)

The Catch

Yes there’s a catch. 🙂 About the Peshitta and Old Syriac versions: They are written in Syriac Aramaic, a dialect that truly crystalized after the lifetime of Jesus and in a different geographical location, so this would not be the exact language that Jesus would have used.

In essence, the catch is that even these (including my text above) would not be the “Original Aramaic” of the Lord’s Prayer.

I know of several reconstructions of the Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic that would be very similar to the dialect that Jesus would have used, given certain assumptions we make about him. However, those will come about on a later date.

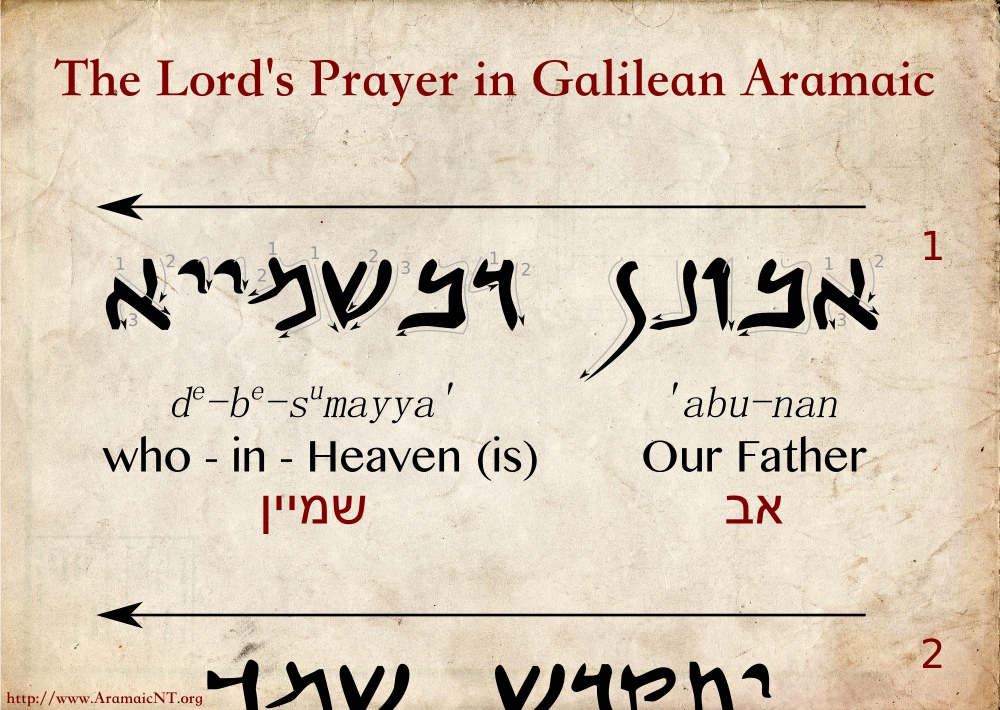

UPDATE November 2012:

I have posted my reconstruction of The Lord’s Prayer here:

|

| The Lord’s Prayer in Galilean Aramaic on AramaicNT.org. |

=============================

Topics covered include:

– A (Brief) History of Aramaic & the Dialect of Jesus

– The Syriac Peshitta Tradition

– Other Syriac Traditions and Their Relations to Each Other

– Scholarly Reconstructions

– Modern Aramaic Traditions

– Odd Translations

– Conclusions, Thoughts & Final Paper

This is a really nice summary of the issues, thanks. I’ve added it to my hall of fame on the subject at http://www.squidoo.com/abwun/

I’m glad that you’ve found it useful. Thanks for linking. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

Here’s another one, Steve, which purports to be what initiated the Matthean version. It’s a prayer to one’s spirit, and comes from the Talmud Jmmanuel.

My spirit, you exist within omnipotence.

May your name be holy. May your kingdom incarnate itself within me, on Earth and in the heavens. Give me today my daily bread, that I may recognize my wrongdoings and the truth. And lead me not into temptation and confusion, but deliver me from error. For yours is the kingdom within me and the power and the knowledge forever. Amen.

Shlama Steve,

sunqânan comes from ‘snq’, to need, to be lacking. Sunqâna is the thing lacking, and sunqânan is that which we lack.

Check the Comprehensive Aramaic Dictionary for this ( http://cal1.cn.huc.edu/ )

Apparently the Greek term ‘epiousion’ dropt out of usage fairly early, or may have simply been an East Mediterranean usage. I have heard that confirmation of usage as ‘daily’ comes from the Oxyrhyncus papyri, and is recorded in ‘Light From the Ancient East or The New Testament Illustrated by Recently Discovered Texts of the Graeco Roman World’ by Adolph Deissmann.

The Sahidic Coptic has ETNHY ‘which is coming’ for ‘epiousion’. I don’t know what the Bohairic says.

The verb ‘snq’ is used in the Peshitta of the Gospel according to John, where it is written that Jesus ‘had no need for anyone to witness to him regarding mankind’

La sniq wa leh d’nash nes’had leh ‘al barnasha.

Push b shaina/Be Well,

Bob Griffin

Bob,

Absolutely correct and good eye!

It’s also a bit ironic. I’m currently in the middle of rewriting this article to submit it to a number of publications and I just noticed it earlier today. What had happened was that I was interrupted with a phonecall at that point in going over it and I suppose that “constant” was stuck in my head.

This is one of the reasons I hate blogs: I don’t edit off the cuff very well. For example, when I’m translating for a client I always take a break and double check my work in a few hours or go at it the next day when my mind is fresh and rested. On blogs, I’ve posted thoughts and have been interrupted, or words that I’ve been typing in the wee hours of the morning, sometimes half-asleep.

This is also one of the reasons I love blogs: Quick peer review. Make a goof, and you have comments. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

An interesting post.

I’m familiar with one difference between Syriac and Classical Aramaic –that a noun in the absolute state in the latter indicates the indefinite article, the emphatic state the definite article — while in Syriac the emphatic covers both and the absolute state has withered down to a few special cases (quantity, etc).

But I was wondering what differences there are between Syriac and Palestinian Aramaic.

After all, so much is common between Syriac and Arabic, that someone who knows the former and none of the latter can travel around the Middle East and make himself understood. These are all related languages in the end.

Syriac did exist in the time of Christ, I think; the earliest Syriac inscriptions (all pagan, of course) are from the 2nd century BC if I recall correctly, written in Estrangelo.

But as far as I know no Syriac literature prior to the 2nd century AD now exists. The pagan literature was prized for its poetry and still existed in the 13th century, but the collapse of Syriac culture after the Mongol invasions ensured the near-extinction of Syriac and the loss of all pagan and much other literature. (I know that you probably know all this, but perhaps not all readers will).

This comment has been removed by the author.

I am glad my Blog posting led to your reply; thank you. I find your comments insightful; I’ve subcribed to your Blog and Bookmarked your sites for future reference.

Peace, Richard

Dear Steve,

Thank you for publishing your insights on the Lords Prayer. I am very new to the study of Aramaic and Hebrew and have just recently read a book on the Aramaic version of the Lord’s Prayer by Rocco Errico. I found the book by chance in a second hand store, and am very glad I did so. It has really expanded and deepened my understanding of the Jesus’ prayer. Here’s Dr. Errico’s version in English as posted on his website. I’m not sure what Aramaic version his translation is based on, but you can see the original text of it along with the below translation on his website at:

http://www.noohra.com/Index.pl?mm/Lords_Prayer

————————

An expanded translation by Dr. Rocco A. Errico:

Our Father who is everywhere

Your name is sacred.

Your kingdom is come.

Your will is throughout the earth

even as it is throughout the universe

You give us our needful bread from day to day,

And you forgive us our offenses

even as we forgive our offenders.

and you let us not enter into materialism.

But you separate us from error.

Because yours are the kingdom, the power and the song and praise.

From all ages, throughout all ages.

(Sealed) in faith, trust and truth.

Shalom,

-Raphael Cavalier

Yes, the text that is posted on the Noohra Foundation’s website is verbatim from the Syriac Peshitta (the version that I’ve posted above). Dr. Errico’s “expanded translation” does seem to go a bit beyond the actual language, itself, but is much closer than some of the other interpretations that are going around the internet.

Some comments:

– Our Father who is everywhere

– …

– even as it is throughout the universe

“Shmaya” means “heavens” or “sky” not “everywhere” or “universe” as it appears above.

– and you let us not enter into materialism.

“Nisyouna” which he renders as “materialism” means “danger” “test” “experience” or “punishment” and in very rare cases can mean “loan” (although it’s in the wrong form, perhaps this is where he got “materialism” from?).

– But you separate us from error.

“Bisha” simply means “evil.” There are a number of Syriac words for “error,” none of which appear here.

– (Sealed) in faith, trust and truth.

This is a bit flamboyant for “ameyn.”

Overall, Errico adds in a number of flourishes that are not completely honest to the language, itself, but he does a fairly good job of rendering things otherwise.

Peace,

—

Steve Caruso

hi can you translate the english word “firend” to aramaic

Very interesting article, although as a complete layman I have to confess I was rather disappointed to find how well your final translation correlates with what Wikipedia calls the 1662 BCP version. One could be forgiven for wanting to find a bit more excitement and variety when digging back two thousand years! I’m sure that desire is part of what some of the more poetic translations are catering to.

One point in partial defense of some of those translations: they make more sense if you imagine that they’re translating not into standard English, but into some more specific dialect, such as “New Age English” (which certainly seems to me to be a distinct and identifiable dialect, whether it’s formally identified as such or not).

In that view, translations like “cosmos” for “heaven” make some sense. The same could be said about the rather clumsy “birther/father-mother” construction: if the language being translated into has a different attitude towards gender, “father” might reasonably be translated into something less specific.

Of course, this view raises questions about accuracy of translations, but those questions exist to some extent in any case: you have to map concepts to their closest equivalents, and the nature of those equivalents are determined to a large extent by the target language and by the understanding of that language possessed by the translator and his/her audience.

Note that I’m not actually arguing that these translations should go unchallenged – rather, I’m pointing out a context in which they could be considered more valid. That context should not be confused with standard English, though.

Hi Steve,

Thank you for these translation details!

I have seen sometimes an additionnal word at:

Ushvuq lan khaubeyn (ukhtaheyn) aykana…

Do you know what “ukhtaheyn” means?

I find it on the Chaldean Church website which still use aramaic.

http://www.mission-chaldeenne.org/prieres.php?priere_id=1

Secondly, what is the best translator for aramaic?!

Many Thanks

Borislav

“khtaheyn” is a Syriac Aramaic word which means “sins.” That makes the version of the prayer on the page you posted read “Forgive us our debts and sins…”

Now as for the best translator, I’m not 100% sure what you mean. I am a bit partial for Aramaic Designs. But perhaps if you gave me more context I could better answer things. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

I am curious about the word “schmaya.” My understanding is that Judaism of the period had not evolved the concept of our “Heaven and Hell,” which would have been added after the introduction of Zoroastrian ideology.

Could you clarify this a bit, please?

hi steve… basically your translation is quite close to what’s currently being taught by the church and not dissimilar…

so the church isn’t conning us, then!

thanks for the clarification — a bit disappointing, though!

cheers

All of this is well and good, but all I see is your critque of others’ work, which disappoints and ranks you with most who criticize but don’t create. You can mitigate this impression by providing *your* translation, corrected to *your* views, and submit it for review by the same type of mindset with which you approached the work of others. Until then, all I see here is someone who missed the point of the prayer so completely there’s not even a hint of Jesus in his commentary.

I guess you know about the Emerald Tablet, then do you have any experience of Calligraphy?

“All of this is well and good, but all I see is your critque of others’ work, which disappoints and ranks you with most who criticize but don’t create.”

If these others put out texts that falsely portray themselve to be translations, there is no need for creativity and criticism is called for.

These people could have used their creativity in a straightforward manner and stated that they wrote prayers of their own. But instead they lie about this. And why? Propably because no one would care about such modern-day prayers.

Jason D:

The concepts of heaven and hell were far from “standardized” within that period of Judaism’s history. There were some groups that believed in a Heaven where others did not, some believed in a Resurrection where others did not, and some believed in oblivion (viewing “Sheol” or the Grave as non-existance) where others believed in a Hell as in a burning pit of fire. As to who believed what first, no one is 100% sure.

Michael Sigmond:

Ah, the Tabula Smaragdina. 🙂 The Aramaic Lord’s Prayer “translations” do very closely mimic the linguistic and logical gap that exists between that Latin text and many of its supposed interpretations.

As for calligraphy, I do quite a bit in both English and Aramaic. 🙂

Resident:

Exactly. If the authors of these “translations” would promote them AS meditations on the prayer (which is what they do seem to be), and not as academic translations that are faithful to the underlying text, there would be little problem.

However, because there is no such disclaimer, I find at least a half-dozen blog posts a month echoing these “authoritative” versions of the “original Aramaic.”

Peace,

-Steve

Hi, Steve. You translated the line “U’la te`lan lnisyouna” as “And don’t lead us into danger.” I’ve read elsewhere the alternative translation is “And don’t let us into temptation.” I know from your blog that the word “nisyouna” can mean both danger or temptation, but how about the verb “te” (lead), can it also mean “let” as claimed by that alternative translation?

Also I’d like to ask about the line “Dsoonqanan yomana”, you tranaslated “yomana” as “daily/everyday”. I’ve seen others translated it as “today”, how accurate is this? Thanks in advance and Merry Christmas 🙂

Ivano,

The verb in question in the phrase “U’la te`lan lnisyouna” is actually “`alal” (the “te-” is the 2nd person masculine singular imperfect prefix) whose Generic (“peal”) form literally means “to enter” but when I originally wrote this article I seem to have interpreted it in the Causative (“aphel”) form which bears the connotation of “to lead” “to introduce” or “to bring.” Since both forms are consonantally identical, I do suppose it could be either “enter” or “lead/bring.” “Let” might work, but only in a similar sense.

As for “yomana” the “-an(a)” suffix in Syriac is a little bit ambiguous. It could mean “daily” or “this day” (the latter a “contraction” of “yom hana”), and upon reconsideration the latter might be the better way to render it overall.

Since these are good points of note, I’ve gone ahead and integrated these alternate explainations into the body of the article. Thanks for bringing them up. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

Steve, thanks for your prompt reply. I still don’t quite get the meaning of “U’la te`lan lnisyouna” clearly. The popular translation of this phrase as “don’t lead us into danger/temptation” is quite problematic. This implies that God is the cause of our entering danger/temptation. I believe this sense of meaning is hard to swallow because tempting people or leading people into danger seems to be the job of the devil, rather than God.

The alternative translation that I mentioned before, “don’t let us enter danger/temptation” has completely different meaning, it suggests that God is the cause of our NOT entering danger/temptation, and surely God, in this sense, is not the one who is tempting or leading us into danger/temptation, instead He’s the one who’s stopping us and pulling us away from it.

How come two contradicting interpretations can stem from the same aramaic phrase? The latter interpretation (with “let”) is claimed to be what the aramaic phrase originally says. I’d like to know if the phrase in aramaic really suggests God as the tempter himself or rather as the one who saves us from temptation/the tempter?

I also would like to know if that phrase could reasonably interpreted as “don’t lead us into punishment”? “Nisyouna” can mean “punishment”, right? The phrase in the prayer before this one is a plea to God to forgive our sins, so it seems reasonable that the next plea would be for God not to punish us. God does punish people and by asking Him to not punish us but instead to deliver us from evil, we acknowledge our weakness against sins and temptation and we need His help to overcome it. So it goes like this: “Forgive our sins as we also forgive sinners, and don’t lead us into punishment, but deliver us from evil.” What do you think? 🙂

I love the info. on this blog about this prayer. I do not know Aramaic so, when I found the other translations I was shocked at the differences. The translations did reflect my personal spiritual insights but they were definitely revealing that the biblical version of the prayer was wrong, including the Greek which I can actually read. But clearly you are saying that the translation was not so wrong after all. I have to ponder on how to correct this on my personal blog postings as I do not want to mislead. Thanks, for pointing me to your blog. I may need to do another blog posting on this pointing to this blog. I hope you do not mind.

Peace!

I think you missed the point ofKlotzes ranslation. You are making the same mistake the Greeks did. You have posed a concrete interpreteation without regard for idiomatic representation and tonal meannigs ( beleive me, after living and learning Thai, I know that there are about three mweanings to each word. And then imgine the poor Japanese visitor who is told “He thinks who the hell he is”- I grew up in the Bronx, I know what it means…but a litteral translation doesnt help them understand. The Japanese have a term called “Mu-Shin” It means no mind. Depending on the idiomatic understanding of the intent it can mean anything from he has no mind (is stupid) to he has a clear mind (is spiritual ). I’ll go with Klotz, but I apprecieate yuor comments.

Mystic and Francesco,

if the English is not a proper rendition of the Greek it is not the fault of the Greek. You cannot say “the Greek is in error” as regards to the prayer’s text. For all practical means, the Greek is the original, even if it was once translated from Aramaic (of which we cannot actually be certain). But who has more expertise on this, the Greek translator who lived at the time or some 21st century geeks who think that “birther of cosmos” sounds cool?

Whether the Greek agrees with your sprituality, Mystic, is another matter, but has zero impact on translation matters as you cannot assume that the original agrees with your spirituality.

Comparisons with totally different languages and language situation do not hold watter either. “Hell” in “what the hell” means exactly what the word always means! It is used a swear word but hell is still the place below. It would be wrong to interpret as referring to something else.

Thanks for this information, I have updated my links accordingly (i.e. removed my link to the nazarene way website and linked to this instead).

I do not see why they couldn’t label their versions as meditations on the original; it would make them more valid, not less.

My version is clearly labelled as my reinterpretation of the prayer.

Yewtree,

Exactly. 🙂

I’ve seen many truly beautiful meditations on the Lord’s Prayer from a wide variety of traditions that try and look at the prayer from different viewpoints and they explain their methodology or the context around their interpretations.

The thing that irks me about these is the inherent (whether intentional or not) deception that their interpretations have some sort of authority because they are “direct translations” from the “original Aramaic” (when in fact there is no “original Aramaic” on record, and they aren’t faithful translations of the texts they work from).

Since Aramaic is such a rare family of languages not many people can point out otherwise. 🙂

As such, you can see how much I really appreciate your honesty on your blog. 🙂

Peace and thanks,

-Steve

Thanks for the article! It helped me when I was not sure what to make of some of the other “translations” from Aramaic. It’s great to have quality material like that available online! Greetings from Prague, Czech Republic

Thanks for this post! Very informative and well written. I stumbled upon that article you’re referring to in your post and couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw that socalled “translation”. Then I saw your comment and found your blog 🙂

Does this mean that Neil Douglas-Klotz’s “translations” of the Beatitudes and his other books such as THE HIDDEN GOSPEL should be viewed, at best, as his meditations and loose interpretations of the Aramaic language (whether scholars have access to it or not) by a gullible person like myself? Are you familiar enough with his work to advise me one way or another?

garyegeberg,

I am familiar enough with the works of Neil Douglas-Klotz to say that the bulk of his work consists of expressions of mysticism, and not of linguistics.

Peace,

-Steve

Thanks for posting this translational discussion, which I found because it’s currently linked from Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord's_Prayer#Aramaic_version

(See the reference at the end of that section.)

Would you mind editing or commenting on this post to include a link regarding your personal (or professional) translational opinion? My campus ministry is interested in learning our closest guess at the words Jesus might have spoken, which you seem to indicate you have some guesses at based on dialect etc.

Along those lines, how faithful is this spoken (and transliterated) Aramaic?

http://www.v-a.com/bible/prayer.html

I recognize that the English version is not quite what I’m used to (eg, “universe”).

Thanks,

annag

I for my part cannot provide any Aramaic expertise but still I might comment on the text linked in the last posting:

The English translation looks pretty much as the standard text everyone knows except for two items, the universe bit and the “serenity” bit. I don’t know about the first, but “serenity” for me sounds too much like avoiding the acknowledgement that one might have sinned, transgressed or be in debt to someone.

A note on the method: the most original text that we have on the prayer IS the Greek one in the New Testament – any aramaic version is either a translation of the Greek or just plain speculation, prone to subjective re-interpretation.

I love the scholarship of this post!!! It is absolutely fascinating, the different derivations of sacred writings and the various influences on their construction. My deepest hope is really this though: That the most outstanding thing about reading “The Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic” regardless of its source, is that it offers a rendition of something very familiar to us that opens up the greater cosmic implications of the words, the ancient culture of early Judaism/Christianity, the identity of the pray-er, and timelessness of the sacred interrelations of life. If we miss this because of the academic nitty gritty, then we have (again) left-brained ourselves out of a chance to experience something sacred. There are those who can hold both and not lose either and those who will use the differences to limit their experience. I am so glad to find your site Steve! thanks for commenting this morning and directing me here! Peggy

The “Aramaic version” is a fraud – there is nothing sacred about it.

I think you miss the point of some of the Klotz posters. Klotz makes definitive, declarative statements about Aramaic that are either true or false. Does the word “d’bwashmaya” have any link to the words “breath” or “cosmos?” If those ideas are, in fact, part of its root, then I fail to see how you can claim that Klotz is so far off the mark. You do not address whether he is correct about the root words, nor do you make the historical case that Aramaic speakers were more literal and disconnected from the roots of their words than Klotz would have us believe. If you expect people to reject renderings of the Lord’s prayer which you find inaccurate, then I suggest you actually…discuss…the inaccuracies… Right? Instead, you make blanket, conclusory statements indicating that other translations are “inane” and untrustworthy without a single fact to back up your point. If they are, in fact, inane and untrustworthy, I’d LOVE to know why. I simply don’t find any answers in this blog post.

@CLWaltrip

Ok, let’s do a little exercise to illustrate what I mean.

If I were to call you “mean” and “awful,” you’d probably be upset with me. However, “mean” has its root in “common” and therefore “humble” where “awful” has its etymological origins in “full of awe.” In Modern English these words are derisive. In a short hop back to KJV English (i.e. the English of the King James Bible) these words were closer to their etymological origins to the point that the translators of the KJV used them to describe their work in a positive light.

Another good example is the word “passion” which can mean “fervor” or “drive” but has its origins in the Latin passionem, which means “suffering” (and the only time it takes on that meaning in Modern English is in reference to the “Passion” of Jesus).

Claiming that the meanings of words can always be tied directly to their etymological roots is known as the “Etymological Fallacy,” which is a fallacy because language evolves.

When Klotz diverges from the “traditional” rendering of the Prayer, he tends to either a) make incorrect claims about root meanings in context or b) make the Etymological Fallacy.

Where I could write a book in response to his Prayers to the Cosmos (which would not be appropriate for a comments thread on this blog) allow me to use the example you’ve given:

“abwun d’bashmaya”

“Our father who is in Heaven.”

vs.

“Our father-mother, birther of the Cosmos.”

“Abba” or “father” in Aramaic does not carry feminine connotations, nor does it carry connotations of birth. If this were the case, we would expect to see it from the root “yalad” which means “to give birth.”

“Shmaya” or “heaven” in Aramaic, where it is a complex concept, doesn’t fit nearly into the word “cosmos.” How do we know this? In Classical Syriac (which is the dialect that Klotz was translating from) “cosmos” was adopted directly as a loan word *from* Greek (“qosmos”) to express the concept. If it meant “cosmos” it would have plainly stated said so.

So you see, to finagle this meaning out of a rather plain statement is “dishonest” *unless* it is in the context of “interpretive meditation” — *not* the context of a “translation” (which it is not).

Peace,

-Steve

I find the curiosity that all of us that have no idea about Aramaic language and its variants to know how it sounds the way Jesus and their followers speak should be nothing more than that, curiosity.

Besides scholars and people who dedicates their lives to study this subject all others should not take too much time to be focused in all these Aramaic translations.

I am for sometime reading the Victor Alexander blog http://www.v-a.com/bible/prayer.html and its Galilean variant, but I have some doubts about this variant.

We can read in Victor blog, this sentence “The translation that you find on this website is made from the original Ancient Aramaic Scriptures directly into English, bypassing the errors of translation introduced in the Greek Original, the Latin Vulgate and all the Western translations made from them.”

And where are those original Ancient Aramaic Scriptures? and are they in Galilean variant?

But I find it very interesting, Victor’s website.

All the best

Mike

I strongly suggest taking anything Victor Alexander has to say about “Galilean Aramaic” with a heavy dash of skepticism as what he’s calling “Galilean” seems to be — in actuality — poorly-pronounced Classical Syriac (a very different Aramaic language, altogether).

Additionally, after numerous emails, tweets, and other attempts at correspondence with him to correct this, he has ignored me (which I find rather suspect).

In either case, I’ve written an article on The Aramaic Blog about it here, outlining the Syriac and where genuine Galilean features are absent:

http://aramaicdesigns.blogspot.com/2010/03/victor-alexanders-aramaic-bible.html

So, in short: Galilean? No. Odd Syriac.

Peace,

-Steve

Thank you, Steve, for this information! I think the most important point brought forward is that there is NO ORIGINAL ARAMAIC TEXT to translate “directly” from! Any claims to be a “direct translation, bypassing any errors from Greek or Latin” have to be false – intentionally or not. Until someone comes forward with a text written in Galilean that dates to the lifetime of Jesus, and not 100 years or more after, any translation is going to be of something other than “the original Aramaic.”

I’m still interested in finding an approximate back-lation into the relevant dialect of Aramaic, should that be feasible. Does anyone here know where such a thing might be found, or how to evaluate the various ones available for probable-closeness-of-approximation?

Thanks,

annag

@annag I go over several reconstructions as well as my own in the ARC010 The Aramaic Lord’s Prayer class on DARIUS.

However, I find myself hesitant to post my own work on the Prayer publicly as it’s (a) always a work in progress and (b) would be the sort of thing that people would grab and reproduce without appropriate context or attribution. In the course there is a *lot* of context to absorb (dialects, culture, scholarly opinions, and the oddball “translations” that exist out there) to set the stage before a reconstruction is meaningful.

Peace,

-Steve

Hi Steve,

I like your point of attacking the “translations” as translations and not theire content.

I´m anthropologist, with no clue about aramaeic, but i´m making research on a religious group, that pray the “our father” as i knew it except that they say “we come to thy kingdom” instead of “thy kingdom come”. They claim that in aramaeic it could have both meanings.

what do you say to this?

thanks for the nice blog, and please excuse the poor english, this posting probably will have because of tiredness.

greetings

Miri

Miri,

you have to keep in mind what’s valid for all these supposed “original aramaeic” issues – there is no aramaeic original anyone knows of, only a Greek original.

Any aramaeic texts are either (more or less accurate) translations from the Greek or they are speculations, often driven by some agenda.

Yes, that i got from this blog 🙂 and i´m still researching where they got their aramaeic version from.

But what i meant with my question was, if “we are comming to your kingdom” and “your kingdom is comming to us” is so similair in aramaeic that (in any text) you couldn´t know for sure how to translate it, or if this would be quiet clear.

kind regards

“and i´m still researching where they got their aramaeic version from.”

They probably made it up.

“… if “we are comming to your kingdom” and “your kingdom is comming to us” is so similair in aramaeic that (in any text)”

I don’t know the language but that would mean that one couldn’t determine whether the subject is “we” or “your kingdom”. Furthermore, the “we/us” needs to be introduced. There is no “to us” in the original text, there’s only “Thy kingdom come”.

Finally, the “we can’t tell in Aramaic” argument, even if true, doesn’t fit as the original is Greek.

thx for the info.

“Finally, the “we can’t tell in Aramaic” argument, even if true, doesn’t fit as the original is Greek.”

Don´t forget i´m in social science on a very grass-root level. in my research the “objectiv truth” doesn´t play any role at all. I´m just researching what they understand as their reality. And there i was interrested, if they realy made the efford to learn aramaeic, or were just repeating something to me, which they got from somewhere and which by being repeated without being doubted may become “objectiv truth” in their circles. For my research this sentence than could be quiet usefull for understanding how “reality” gets created in the group, like who has to confirm an information, so that all accept it. The source of this sentence is probably playing an important role than in this process.

If in aramaeic this realy would have been interchangable, than i can´t realy say anything about that, because i don´t know if the people doubted that persons information, and are just repeating it after it proofed right after their own research…..before i bother you too long with that. I just say thank you for fast responds.

@tontobius “if you imagine that they’re translating not into standard English, but into some more specific dialect, such as “New Age English”

Is an idea i that´s quiet helpfull, for my work. Does anyone know if there is some proper work done on “New Age”-speak

@Miri Has –

“but i´m making research on a religious group, that pray the “our father” as i knew it except that they say “we come to thy kingdom” instead of “thy kingdom come”. They claim that in aramaeic it could have both meanings.

what do you say to this? “

Interesting question.

The short answer:

No, this is not possible.

The long answer:

In Aramaic, “Your Kingdom come” would be some permutation of tithe malkutakh. In order for any such ambiguity to exist, malkutha (“kingdom”) would need to be grammatically masculine, which could then change the verb to the masculine form nithe, which could be either “he/it will come” or “we will come” (they are homophones and homographs).

However, here’s the BIG caveat: This form only exists in certain Eastern dialects such as Syriac, Mandaic, and often in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, etc.

In the dialect that Jesus spoke (Galilean, a Western dialect) the masculine verb form is the older form, yithe, and shares no ambiguity with the 1st person plural.

Additionally, there would need to be an accusative particle le- affixed to malkuthakh to indicate “to your kingdom,” otherwise it would simply say “We will come, your kingdom” which makes no sense. 🙂

I fear that this group you are studying is relying upon a sliver of truth steeped in misunderstanding.

Now that made things clearer to me. Thanks a lot

Thank you for this translation. I was misled by this facebook post:

The Lord’s Prayer

O cosmic Birther of all radiance and vibration. Soften the ground of our being and carve out a space within us where your presence can abide.

Fill us with your creativity so that we may be empowered to bear the fruit of your mission.

Let each of our actions bear fruit in accordance with our desire.

Endow us with the wisdom to produce and share what each being needs to grow and flourish.

Untie the tangled threads of destiny that bind us, as we release others from the entanglement of past mistakes.

Do not let us be seduced by that which would divert us from our true purpose, but illuminate the opportunities of the present moment.

For you are the ground and the fruitful vision, the birth, power, and fulfillment, as all is gathered and made whole once again.

Amen

(Directly translated from the Aramaic into English, rather than from Aramaic to Greek, to Latin, to old English, to modern English)

I love the sentiments of this new prayer, but wondered about the disparity between what it said and the translation I grew up with in the catholic church. I know that translations can vary, but this was so different that it made me curious and inspired a desire to research it. I find it disgraceful to present these translations as more “true” to the actual aramaic if they are not. I think they should definitely be making a disclaimer that notes poetic license may have been used.

Thank you for being clear and for making things clearer for me.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge… I got so happy to find your blog but was really hopeful that Jesus mentioned any Mother of the Universe and any other esoteric spells… what a pity.

It is exactly how we pray it in Portuguese nowadays, Catholic Church…

MJ

Steve,

Can you comment on Mark Hathaway’s clear and detailed explanation as to the meanings of (what is) your translation of the Aramaic? He explains how Translations 2 and 3 above are conceived, but does not claim that they are the only translations. His explanation seems eminently reasonable to me.

Link: http://www.visioncraft.org/aramaic/intro.htm

Thanks. Namaste,

E.J.

“More importantly, though, Aramaic texts of Jesus’ words have been preserved by the Eastern churches.”

No, they haven’t.

“While scripture scholars usually maintain that the New Testament was written first in Greek”

And they are right. There might be Aramaic predecessors but they have not survived.

“there are good reasons to believe that the Aramaic text (known as the Peshitta) may more accurately reflect the words which Jesus himself spoke.”

If it does, then the Greek is even more accurate because the Peshitta happens to be an Aramaic translation of the Greek NT.

So much for the knowledge – and credibility – of this “ecologian”.

It is no big surprise that he identifies “creating the universe” with “giving birth”.

Have you heard of the theory that the best rendering of the Aramaic Lord’s Prayer may be found in the Latin Vulgate?

Jerome claims that he used the oldest Aramaic or Jewish (Aramaic?) version of Matthew he was able to find in the Fourth Century, to make his translation. That is why all Catholic versions of Matthew end the prayer at “deliver us from evil” rather than including the extended ending, as does the Peshitta, which most scholars agree was not in the original manuscript.

Thank you for your scholarly viewpoint concerning those New Age versions that seem to be popping up all over.

I’m a latecomer to this party 🙂

As a beginner I’v a few Q –

If you have a background in Arabic – you’ll know that ‘wa’ means ‘and’

[the original aramaic prayer you posted at the beginning of your post – only the translation is spurious not the prayer I suppose]

Dont you think wa-haila wa-teschbuchta ] might be closer to the real deal than your translation – Ukhaila utheshbookhtha –

I’m inclined to think so!

please check out this video-

-most syriac renditions go Abwoon d’bwashmay’o’,chichi meltuithe etc while this doesnt –

This might be closest to the Aramaic that Jesus spoke [ not to galilean of course but to at least what other aramaic speakers were speaking @ that time]

As a researcher please do pen your thoughts on the subject,what do you think?

This is a fantastic article!

I saw those “cosmic translations” for the first time yesterday on a facebook fanpage. I couldn’t believe my eyes that the people there thought them to be accurate and oh-so-enlightening. Probably the most upsetting thing is that even though you provided here an extensive commentary, people still are able to quote bits and pieces from your article to reassure themselves that the translation of the Lord’s Prayer is uncertain, can be questioned and the direction of “the cosmic translations” is especially desirable. Maybe they just don’t have good enough English to really understand your point (discussion was in Polish)…

It’s a pity that my Syriac is poor and dying (a year’s break from learning). If I ever need any linguistic commentary on Aramaic, I’ll be sure to look for your blog first for the background reading 🙂

Thank you very, very much.

As a minister who’s considered on the border of heresy (i.e. an Independent Catholic Priest) I am often asked about the ‘Original Aramaic Lord’s Prayer’ and although, like you, I have no problem with people finding a prayer that works for them I’ve never before found a website that explains how it isn’t what they say it is so very clearly and helpfully.

Bless you. I shall post this on Facebook.