As I’ve mentioned before on this blog, when it comes to Aramaic materials sometimes you can judge a book by its cover.

In this case, it is also a prime example of how a Google search can go terribly wrong. 🙂

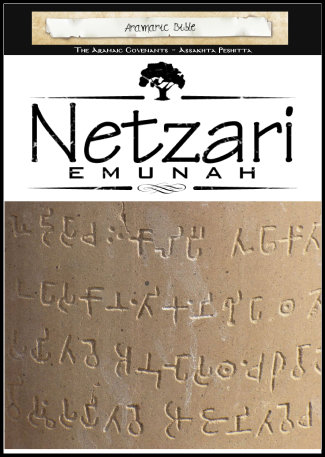

Long story short, I came across this book cover a few days ago:

If you can’t make out the text at the top, it reads: “Aramaic Bible: The Aramaic Covenants • Aramaic Peshitta.” Here is an excerpt from this book’s website:

This work is a new edition from translations of the Ancient Aramaic. For example this new edition uses the name of MarYah Eashoa Msheekha (Lord Yeshua Messiah). It also uses the word Allaha for HaShem (G-d). The Ancient Aramaic translates the correct name of ‘Eil witch refers to the ‘Absolutely Eternal’ Allaha, and it introduces the Aramaic rendering of Maran for Lord, Along with other Ancient Galilean Aramaic renderings.

So let’s take a moment to pick this apart and make some sense of it. I could be wrong, but the Netzari website appears to be a Messianic sect in the Sacred Name Movement persuasion that has produced a “new edition” from (apparently) extant translations of Aramaic texts where the names have been changed to (rather poor) transliterations of late Classical Eastern Syriac terms because they — among others — are “Ancient Galilean Aramaic renderings.”

Despite… serious methodological problems, I can at least navigate around all of that and make sense of it… but there is one glaring problem that I don’t get:

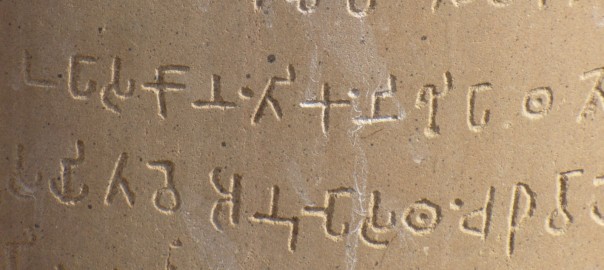

Why is there Brahmi text about Buddhism on the cover of an Aramaic book about Messianic Christianity?

Yes, that wonderful carved text is in Brahmi script from one of the Edicts of Ashoka at Sarnath — official declarations issued in the 3rd century BCE in effort to spread Buddhism. Many of the Ashoka inscriptions were bi- or tri-lingual… and this is where the Aramaic confusion comes in.

When this image was originally uploaded to Wikipedia, it was under the title “Aramaic Inscriptures in Sarnath.jpg“. Whoever uploaded it simply made a mistake, as one of the languages that Ashoka did use from time to time was Imperial Aramaic. This image, however, simply wasn’t such an example, so the author subsequently corrected this mistake by changing the description to “Inscription in Brahmi on the pillar of Sarnath.” (Scroll down on the Wikimedia page, you’ll see it.)

However, guess which title Google Image Search snapped up?

As of writing this, if one simply searches for “aramaic” in Google Image search, this is the first nice looking carved inscription that appears in the search results, about half way down the page. Earlier it was much higher, and because of this it has caused all sorts of delightful confusion.

Now, if someone is trying to produce a “translation” of the Aramaic New Testament to help spread their faith in Christianity, but they can’t tell Aramaic apart from an inscription in a different language which just so happens to be about spreading Buddhism that they came across on Google — perhaps they should reconsider what they’re up to. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

UPDATE: They seem to have taken the hint, and have changed their book cover to a much more boring red-ish-thing. However, they are still going through with publishing it…