Hello Aramaic enthusiasts. 🙂

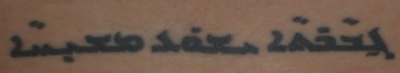

Today I came across the above tattoo on DeviantArt. The owner says that he put the calligraphy together himself and that it is the word “malek” which means “king.” If one takes a close look at it, he is (for its intended purpose) correct.

However, this tattoo is another excellent example of how ambiguities can crop up when certain aspects of the written language aren’t fully taken into account (which unfortunately by empirical observation happens more often than not). There are three of these observations I’d like to make:

1) Letter Scale

This tattoo is written in Syriac script, and one interesting quirk about Syriac script is that certain letters are disambiguated by the length and angle of their stems. In this case, the center letter which should be lamad (the Aramaic equivalent to “L”), is a bit ambiguous and caused me to pause the first time I glanced at it.

This tattoo is written in Syriac script, and one interesting quirk about Syriac script is that certain letters are disambiguated by the length and angle of their stems. In this case, the center letter which should be lamad (the Aramaic equivalent to “L”), is a bit ambiguous and caused me to pause the first time I glanced at it.

Lamad is usually disambiguated from ‘e (a sharp “UH” in the back of the throat) and nun (“N”) by it’s height and angle. This lamad, however, looks very much like how one would expect an ‘e to be written.

2) Diacritical Marks

When writing in Syriac, there are a number of diacritical marks that are used to indicate vowels, when different letters take on different sounds, as well as parts of speech in largely unmarked manuscripts. The dot that we find under what was intended to be a kaf (an Aramaic “K”) is distracting.

In a marked text, a dot under a kaf means that it changes its sound to something similar to the CH in “Bach” (like lightly clearing your throat). However, this convention is usually undertaken when all of the vowels are written (so we would expect to see marks over the mim and lamad for the “a” and “e” vowels).

So here comes the ambiguity: In Eastern Syriac vowel pointing, a dot under a small tick could represent a “long” yud (the Aramaic equivalent to “Y”, but when long like “ee” in “free”). This would break down the word so it would be pronounced “muh-EEK” (if the ‘e ambiguity persists) which in some dialects of Aramaic means “squeezed one” or the word “mah-LEEK” which is not a word at all. Either case, they’re not quite what the author was after.

3) Word Form Finally, and this is more of a stylistic choice when getting a tattoo, but the Absolute form of the word was used where, in Syriac and modern Assyrian dialects, one would expect to see the Emphatic. The Emphatic form, is spelled a bit differently, with one additional letter and a different form for kaf (as now it is no longer at the end of the word).

Finally, and this is more of a stylistic choice when getting a tattoo, but the Absolute form of the word was used where, in Syriac and modern Assyrian dialects, one would expect to see the Emphatic. The Emphatic form, is spelled a bit differently, with one additional letter and a different form for kaf (as now it is no longer at the end of the word).

Conclusion

Overall, this (when examined closely) does express what the author was after, albeit with a little effort. It is a form of the Aramaic word “king” provided one reads the middle letter correctly and is not confused by the stray diatric mark. However, it could have been a bit cleaner, and sending it by a professional to ensure its accuracy before committing to a tattoo would have caught these ambiguities.

Peace,

-Steve