The Lord’s Prayer is with little debate the most significant prayer in Christianity. Although many theological and ideological differences may divide Christians across the world, it is a prayer that unites the faith as a whole.

Within the New Testament tradition, the Prayer appears in two places. The first and more elaborate version is found in Matthew 6:9-13 where a simpler form is found in Luke 11:2-4, and the two of them share a significant amount of overlap.

The prayer’s absence from the Gospel of Mark, taken together with its presence in both Luke and Matthew, has brought some modern scholars to conclude that it is a tradition from the hypothetical Q source which both Luke and Matthew relied upon in many places throughout their individual writings. Given the similarities, this may be further evidence that what we call “Q” ultimately traces back to an Aramaic source.

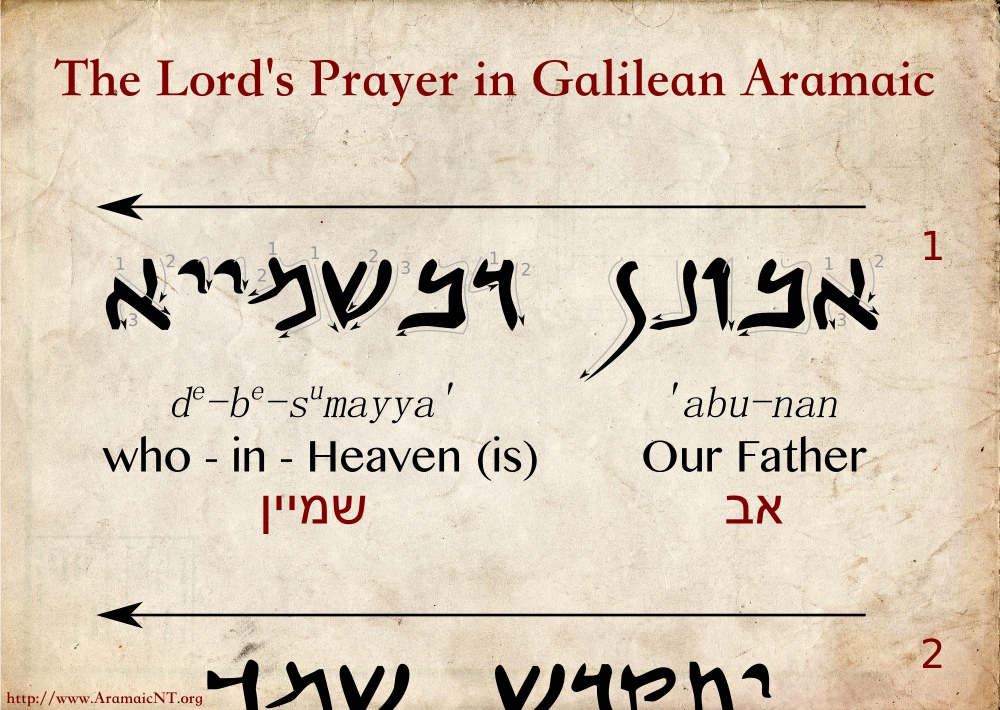

Looking at the underlying Greek text of both sources, and working from what is generally accepted as the earliest form of the prayer, the following unfolds in translation back into Galilean Aramaic:

Abba, [1]

Father,Yəṯqadaš šəmaḵ.

May thy name be holy.Teṯe malḵuṯaḵ.

May thy kingdom come.Tehəwe raˁuṯaḵ.

May thy will be done.Pitṯan də-ṣoraḵ [2] hav lan yoməden.

Give us today our needed bread.wa-Švuq lan ḥovenan. [3]

And forgive us our debts / sins.Heḵ ‘ənan šəvaqin lə-ḥaivenan.

As we forgive our debtors.wə-La taˁel lan lə-nisyon.

And lead us not into temptation.Amen.

Keep in mind that this rendition is a work in progress and will continue to be refined (as any effort in reconstruction should be).

1) Abba, Father

In the most primitive form of the Prayer, God is simply addressed as Father, which in Aramaic is /abba/. Despite common mythology, /abba/ does not mean “daddy,” and was used by children and adults alike. /Abba/ is preserved transliterated into Greek letters (αββα = abba) in three places in the New Testament and each time it appears it is immediately followed by a literal Greek translation (ο Πατηρ = ho patêr).

- Mark 14:36 – He said, “Abba, Father, all things are possible to you. Please remove this cup from me. However, not what I desire, but what you desire.”

- Romans 8:15 – For you didn’t receive the spirit of bondage again to fear, but you received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, “Abba! Father!”

- Galatians 4:6 – And because you are children, God sent out the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying, “Abba, Father!”

Additionally, there are a number of other places where Jesus or others would have used /abba/ in direct address to either God or their own father worldly father (some of which parallel the three above) but in these cases they are only preserved in Greek.

- Matthew 26:39 – He went forward a little, fell on his face, and prayed, saying, “Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass away from me; nevertheless, not what I desire, but what you desire.”

- Matthew 26:42 – Again, a second time he went away, and prayed, saying, “Father, if this cup can’t pass away from me unless I drink it, your desire be done.”

- Luke 15:12 – The younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me my share of your property.’ He divided his livelihood between them.

- Luke 15:18 – I will get up and go to my father, and will tell him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in your sight.

- Luke 15:21 – The son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in your sight. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’

- Luke 16:24 – He cried and said, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue! For I am in anguish in this flame.’

- Luke 22:42 – saying, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done.”

- Luke 23:34 – Jesus said, “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they are doing.” Dividing his garments among them, they cast lots.

- Luke 23:46 – Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” Having said this, he breathed his last.

- John 17:1 – Jesus said these things, and lifting up his eyes to heaven, he said, “Father, the time has come. Glorify your Son, that your Son may also glorify you;

- John 17:5 – Now, Father, glorify me with your own self with the glory which I had with you before the world existed.

- John 17:11 – I am no more in the world, but these are in the world, and I am coming to you. Holy Father, keep them through your name which you have given me, that they may be one, even as we are.

- John 17:21 – that they may all be one; even as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be one in us; that the world may believe that you sent me.

- John 17:24 – Father, I desire that they also whom you have given me be with me where I am, that they may see my glory, which you have given me, for you loved me before the foundation of the world.

- John 17:25 – Righteous Father, the world hasn’t known you, but I knew you; and these knew that you sent me.

(It is curious to note that the only place in the Gospel of John that Jesus directly addresses God as Father in chapter 17. At all time prior or afterwards, he always refers to God as “Father” in the third person. Never in direct address.)

2) Daily Bread

2) Daily Bread

One of the trickiest problems of translating the Lord’s Prayer into Aramaic is finding out what επιούσιος (epiousios; usually translated as “daily”) originally intended. It is a unique word in Greek, only appearing twice in the whole of Greek literature: Once in the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew, and the other time in the Lord’s Prayer in Luke.

This raises some curious questions that have baffled scholars. Why would Jesus have used a singular, unique Greek word? In more recent times, the bafflement has turned to a different solution. Jesus, someone known to have spoken Aramaic in a prayer that was originally recited in Aramaic, would not have used επιούσιος, originally at all, so the question has evolved to “What Aramaic word was επιούσιος supposed to represent?” It would have to be something unique or difficult enough that whoever translated it into Greek needed to coin a word to express or preserve some meaning that they thought was important, or something that they couldn’t quite wrap the Greek language around.

The best fit for επιούσιος is probably the word /çorak/. Where it comes from the root /çrk/ which means to be poor, to need, or to be necessary. It is a very common word in Galilean Aramaic that is used in a number of senses to express both need and thresholds of necessity, such as “as much as is required” (without further prepositions) or with pronominal suffixes “all that [pron.] needs” (/çorki/ = “All that I need”; /çorkak/ = “All that you need; etc.). Given this multi-faceted nature of the word, it’s hard to find a one-to-one Greek word that would do the job, and επιούσιος is a very snug fit in the context of the Prayer’s petition. This might even give us a hint that the Greek translator literally read into it a bit.

/yelip/ is another possible solution for. It is interesting to note that it comes from the root /yalap/ or “to learn.” Etymologically speaking, learning is a matter of repetition and routine, and this connection may play upon regular physical bread, as well as daily learning from God (i.e. that which is necessary for living, as one cannot live off of bread alone).

Moving further along on this line of the Prayer, where the most common word for “bread” in the Aramaic language family as a whole is /lahma/, the most common word for “bread” in Galilean is /pithah/ (cognate to “pita bread” in English, although not that specific). This does not imply that /lahma/ does not occur in Galilean. It is simply far, far less common. Additionally, some times /pithah/ appears as /pisah/ (the th perturbing to s), although this, too, is uncommon and is mostly found in rather late portions of the Palestinian Talmud.

3) And Forgive Us Our Debts/Sins

In nearly every Aramaic dialect contemporary to Jesus, the most common word for “sin” was synonymous with the word for “debt” which is /hob/. When inflected and declined as /haib/ it then takes on the meaning of “one who is in debt” or “one who sins.”

Furthermore, there were generally two words used for expressing “to forgive.” The first one is /sh‘baq/, coming from the root “to allow, to permit, or to forsake,” where the second one is /shrey/ which comes from the root “to dwell, to loosen (as in to unpack)” (taking it’s meaning from the latter). In liturgical formulae, they are used in tandem ( /shrey w-sh‘baq l-hobin/ = “loosen and forgive sins”), but either can be used by itself to express the same thing (much like how “permit” and “allow” are used interchangeably in English).

What is even more interesting to consider, is that a third wordplay is entangled with /haib/, as it is also — in its declined forms — nearly identical to one of the words for “love” /hibah/ which comes from the root /h‘bab/. In the Parable of Two Debtors (found in Luke 7) Jesus demonstrates this pun:

“A certain lender had two debtors (haibin). The one owed five hundred denarii, and the other fifty. When they couldn’t pay, he forgave (sh‘baq or shrey) them both. Which of them therefore will love (h‘bab) him most?”

Note the parallel to the Prayer. Not only is the same pattern with forgive used, but debt and love are held in parallel. This opens up some interesting potential meaning in the prayer:

“And forgive us our sins, as we forgive our loved ones.”

Which is quite a powerful statement. Whether or not this was intentional, however, may never be known. Next…

If you choose to Support the Project, you can view and participate in the following additional content:

- All of the Supporter content on the rest of the site.

- The Prayer written in Aramaic handwriting contemporary to Jesus and his followers.

- An audio recording of how it could have sounded when spoken among early Christians.

- The full ARC010: The Aramaic Lord’s Prayer class from DARIUS that includes the following topics:

-

- What is So Special About the Lord’s Prayer?

- A (Brief) History of Aramaic & the Dialect of Jesus

- The Syriac Peshitta Tradition

- Other Syriac Traditions and Their Relations to Each Other

- Scholarly Reconstructions

- Modern Aramaic Traditions

- Odd Translations

Curious to now if any other up dates are available.

Thanks

There will be more updates soon, I promise. 🙂 I’ve just been exceedingly busy.

Peace,

-Steve

That’s a great work. Is the picture galilean aramaic too ?

Is it normal that the first word is plural (abunan = our fathers) and that d-b-sh-m-y-h has three shewas?

And what’s the root of T’hey, taw he yod yod ?

Thanks for that

Everything here is in Galilean unless otherwise noted. 🙂

The plural for Abba in Galilean is a bit more irregular than in some other dialects. אבונן is the singular (“our father”). “Our fathers” would be אבהתן.

Unstressed syllables in Galilean tend to reduce to half-vowels or all the way to simple shwas, which is why דבשמייה (alternatively written דבשמייא) is vocalized that way.

תהי is a shortened form of the imperfect 3rd person plural form of the verb הוי (to be). In Galilean there is actually a split dialectical feature. Some Galilean texts retain the ו in all inflected forms where others omit it entirely (hence תהי is also spelled תהווי).

Hope this helps,

-Steve

Hey Steve!

I just wanted to thank you for what you are doing, you can’t imagine how glad I am to have found this marvelous project, I myself love learning and studying new languages and religions.

May the Ruach HaKodesh be with you always,

Deo.

Hi, Steve.

I really, really like that you used rˁw, rˁwtˀ for will, desire in ‘thy will be done.’ Do any other reconstructions use this root? It is odd, however, that you include it in the Lukan or Q version since the better Greek manuscripts of Luke do not include this line. I know some of the later Syriac text traditions include the line in agreement with the Byzantine text. Do you intentionally include it because you think it was original to Jesus, Q, or Luke, or did you just want to use the rˁw, rˁwtˀ root?

Thanks, Robert

Robert,

You’re the first one who has actually noticed my decision to keep this line in even when its provenance is largely Matthean. 🙂

I feel it gives a good parallel in the Prayer and in recitation it seems odd or lop-sided without it (at least the way that I divvy up the lines). As such I must admit that the inclusion is probably one of the most aesthetic choices I’ve made in my rendition here. Another reason I believe that it’s more likely original than not (albeit slightly and at least in early recitation) is a parallel in the pericope where Jesus prays in Gethsemane (Mark 14:36 / Matthew 26:39,42 / Luke 22:42; and as an interesting thing of note, in the Markan record “Abba” is even preserved in transliteration). Namely the theme of “thy will be done” is very solid in the Gospel tradition. Ultimately, though there is no way to be sure if the line was there or not.

Separately, I also have to admit that (aside from the fact that it is, by several metrics, in my opinion the best choice in this context) I like rˁwtˀ. Especially its etymological origins. 🙂

Peace,

-Steve

Steve, if you have the time could you please tell me how correct or incorrect this version is?

http://nonharmingministries.com/wp-content/uploads/lordsprayer_aramaic.png

I ask because I am looking for the closest possible thing to the Lord’s Prayer in the Lord’s language, for a tattoo. I do not get tattooed unless I am sure the art is and will always remain extremely meaningful to me. I cannot think of anything more meaningful, and thus I want to get it exactly right and will not waltz into a tattoo shop with something I think might be “close enough.” I have combed through this site in search of your full reconstruction of the prayer in Galilean Aramaic script, but I have only been able to find the first line: Our Father, who is in heaven. Please help, if you have a few spare moments. Thank you kindly, sir, and peace be with you.

I also present these as possible candidates, but am in the dark as to which might best suit my need. I should add that I, myself, know nothing of this beautiful language, hence my seeking your expertise and your advice. Thank you once again.

http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/apostolides/syriac.jpg

http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/images/syriac-l.jpg

אַבָּא

יִתְקַדַּשׁ שְׁמָךְ

תֵּיתֵי מַלְכוּתָךְ

לַחֲמָן דְּמִסְתְּיָא

הַב לָן יוֹמַא דֵן

וּשְׁבֹק לָן חוֹבֵינָן

כְּדִי שְׁבַקְנָן לְחַיָּבֵינָן

וְלָא תַּעֲלִנָּן לְנִסְיוֹן

I offer my sincerest apologies for this third post in a row, but each step of my search uncovers more renderings which appear potentially legitimate. By now, I’m sure my complete and utter confusion is evident. Again, thank you Steve and I’m sorry for crowding up your site with these pesky posts.

http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/images/aramaic1-l.jpg

http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/images/aramaic2-l.jpg

Ahoy Joe,

Checking out the last two images you sent over, they both appear to be closer to the dialect of Targum Onqelos and Johnathan (making use of /-nah/ as the 1st person plural pronominal suffix “our”), so not Galilean.

Peace,

-Steve

Ahoy Joe,

The first three images you’ve linked to are in Classical Syriac, which is a dialect that is about 200-300 years too young for Jesus’ time. The third one you’ve posted, looks like it was done by Ruslan Khazarzar, which is certainly a lot closer (and in fact quite close to my own rendering) but doesn’t take into account a number of orthographical and vocabulary advancements expounded upon by Sokoloff and Kutscher. It also uses the vocalization conventions found in Targum Onqelos which actually represents a number of features that probably wouldn’t have been in use in Jesus’ time, and you would need to remove the Tiberian vocalization markings anyways.

Overall, however, I cannot stress strongly enough the pitfalls of nabbing something off of an Internet search and using it as the basis of a tattoo. This is why the latest revision of my own rendition of the prayer (which includes a tattoo stencil) is currently available up on Aramaic Designs (a professional translation service) here:

http://aramaicdesigns.rogueleaf.com/product/the-lords-prayer-in-galilean-aramaic/

Peace,

-Steve

Thank you for the link, the information, and the prompt reply. You have certainly helped me, and I will be happy to purchase the kit at the link you’ve provided for the most accurate tattoo possible. My only concern is that you’ve referred to this as your latest revision. Is there another revision coming soon and should I wait for it before making my purchase? Also, I know this one may be tricky to answer, but do you think there can or will ever be a definitive revision?

Ahoy Joe,

The latest revision is over on Aramaic Designs. I’ll be updating the page here to reflect it soon.

Like with all reconstructions there is always a matter of fine-tuning things over time. One may come across a better-attested spelling or some minor details. In truth the Prayer probably went through a number of different revisions before the formal form was settled upon as found in Matthew, Luke, and the Didache, so we will never know *precisely* how Jesus spoke it. However, the reconstruction I’ve put together is — in my opinion — probably as close to the form recited by early Christians as we may be able to get within our lifetime (barring some major hitherto unknown discovery).

In that vein, the Prayer that I have here is just as “accurate” as the one over on Aramaic Designs. The only things that have changed are small orthographical revisions and slight vowel quality changes which are things that are within the tolerance of how the Prayer would have been recited in antiquity.

Peace,

-Steve

Tangentially related:

on YouTube, there is an Aramaic (Chaldean) translation of the Christmas carol “O, Come All Ye Faithful” — http://youtu.be/gIwPBD2KB9U —

so …

have you ever translated any Christmas carols into Palestinian Aramaic?