All images found in this article are being used under the doctrine of Fair Use.

All images found in this article are being used under the doctrine of Fair Use.

Prayers of the Cosmos is one of the cornerstone books of the Aramaic Mysticism movement, which has created a number of interesting loose interpretations of the Lord’s Prayer that I have discussed earlier in my writings. It is written by Dr. Neil Douglas-Klotz, a Sufi mystic who has been into Aramaic for (as far as I am able to tell) decades. The book, itself takes the Lord’s Prayer and expounds upon it through modern New Age interpretation, stretching out a few verses of text from Matthew (as found in the Syriac Peshitta) into 112 pages.

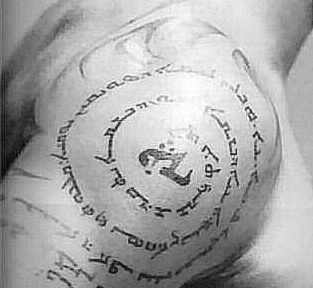

However, the book’s cover displays something rather interesting that I think would have been caught before. The Syriac text is typeset backwards. Take a closer look:

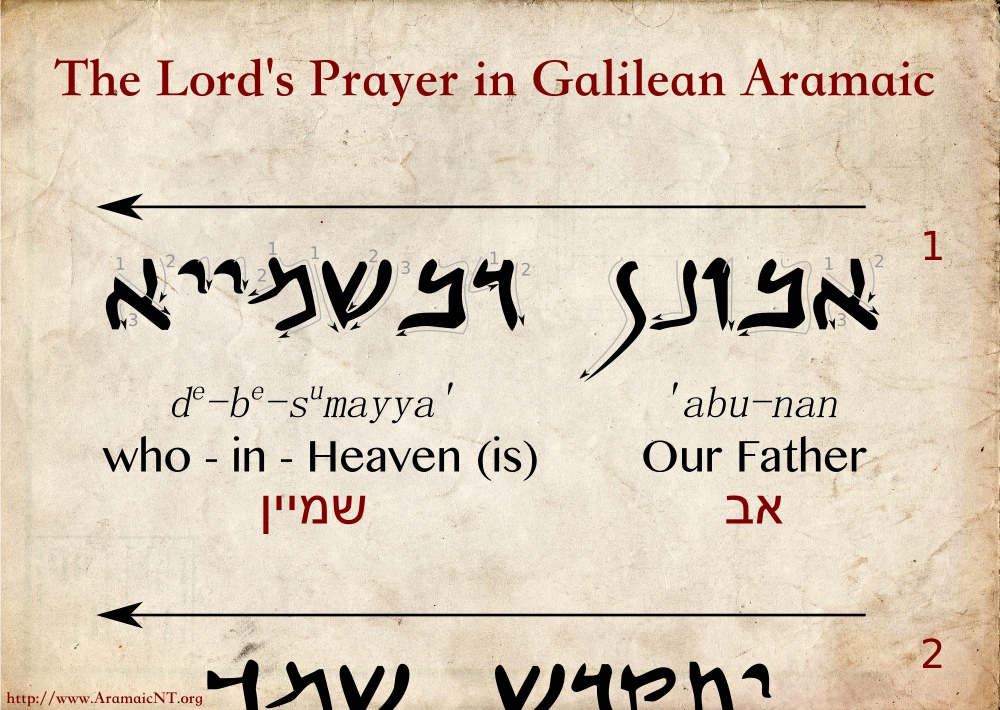

The image is mirrored. It should look like:

The image is mirrored. It should look like: The above reads yeshua` mshîkhâ (Jesus the Messiah).

The above reads yeshua` mshîkhâ (Jesus the Messiah).

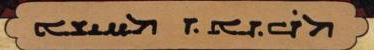

As found on the book cover on the bottom: Again, the image is mirrored. It should look like:

Again, the image is mirrored. It should look like: The above reads mshîkhâ d’medhbrâ (Messiah of the wilderness).

The above reads mshîkhâ d’medhbrâ (Messiah of the wilderness).

Now if the cover was not enough of a tipoff I must admit that the contents are a bit over the top. I have said before and stand by my previous statements about Mysticism being a beautiful form of religion that everyone has in their religious practice to varying degrees (many people don’t even realize it); but I find this book going too far from an academic standpoint in the minutia and granularity that Klotz uses. For example, this is his final breakdown of the word ܐܒܘܢ âbwun:

A: the Absolute, the Only Being, the pure Oneness and Unity, source of all power and stability (echoing to the ancient sacred sound AL and the Aramaic word for God, Alaha, literaly, “the Oneness”).

bw: a birthing, a creation, a flow of blessing, as if from the “interior” of this Oneness to us.

oo: the breath or spirit that carries this flow, echoing the sound of breathing and including all forces we now call magnetism, wind, electricity, and more. This sound is linked to the Aramaic phrase rukha d’qoodsha, which was later translated as “Holy Spirit.”

n: the vibration of this creative breath from Oneness as it touches and interpenetrates form. There must be a substance that this force touches, moves and changes. This sound echoes in earth, and the body here vibrates as we intone the whole name slowly: Ah-bw-oo-n.

(pages 13-14, emphasis original)

From a Mystic’s interpreted standpoint, this makes clear and perfect sense as creative metaphor and something to meditate on. Outside a Mystic’s context, more specifically from a scholar’s standpoint, this is 100% Certified Rubbish™, because to translate ܐܒܘܢ âbwun as anything else but “our Father” is categorically dishonest as it is a very simple and historically documented construction of ܐܒܘ (abu; “father” in the construct state) + ܢ (-n; 1st person plural personal suffix, “our”). Klotz doesn’t seem to give too much in the lines of a disclaimer which is where I personally find a problem.

It is also even more interesting to note that due to dialect issues, if Jesus were to say “our father” it probably would have sounded more like “abunân” and looked more like אבונן when written down (as Syriac was not the dialect of Galilee and Judea).

In the end, for a Mystic, it really should not matter, as a Mystic’s “job” (per se) is to seek out direct experience with God through whatever path or method they choose to use. With that in mind, I’d prefer that Mystics who invest their focus, time, energy and faith into these interpretations of the Aramaic language be aware of the academic problems inherent to what this book details.

So, the next time you come across an “original Aramaic translation,” you know where this Aramaicst stands.

Peace,

-Steve