Before I begin: I am using snippets of content from this document to illustrate problems found both in adherence to and under the protection of Fair Use Doctrine and the First Amendment in ways that have precedent in American law. In doing so I shall take steps to ensure that the content owner’s copyrights are respected and that the heart of their work is protected.

Introduction

This is a review of the Aramaic Tattoo eBook as found on My-Aramaic-Tattoo.com.

Since I posted my first review, I was sent a lengthy Cease and Desist that I pull my blog posts down for a variety of reasons. Within my rights I have made the decision to write this more concise and to-the-point article instead, which bespeaks the problem in more articulate and succinct language, so that my full meaning can be understood.

I will go over each point about the eBook, fact by fact to expound upon my good-faith opinion that it is not a good buy in its current form because it contains errors and lacks important information that, as a result, would not allow a consumer to make an informed decision.

Without further ado, let’s take a look:

At a Glance

For $29.00 over at My Aramaic Tattoo.com, one can obtain a copy of the “My Aramaic Tattoo eBook” which on its website is advertised as “the most extensive and unique collection of Aramaic tattoo designs available” filled with “popular and unique Aramaic tattoo words and phrases.”

Looking about the Internet for more information about it, I found a few advertisements. On EzineArticles.com it was also claimed that “The inspirational Aramaic tattoo design eBook was written and designed to help people avoid carrying mistakes on their bodies for the rest of their lives.”

On PeopleStillRead.com, BalmelPublishing.com and ArticlesBase.com it was claimed that: “we hope that many will use and enjoy this eBook, and will be able to walk proudly with accurate and correct Aramaic tattoo designs.”

After some serious friction with the book’s author, who would not provide their credentials or evidence of their expertise, I eventually purchased a copy in order to examine exactly what they were selling.

Leafing through the PDF I took an initial count of its contents:

It was 70 pages in length.

It had 39 individual words. (labeled: “faith,” “beloved” (m), “beloved” (f), “forever,” “soul,” “love,” “truth,” “health,” “friendship,” “joy,” “freedom,” “peace,” “hope,” “Jesus,” “Christ,” “flame,” “dream,” “life,” “gem,” “light,” “strength,” “paradise,” “holiness,” “dance,” “beauty,” “heaven,” “lion,” “lioness,” “dawn/twilight,” “sunrise,” “star,” “resurrection,” “truth,” “grace/goodness,” “music,” “father,” “mother,” “son,” “daughter”)

It contained 16 Bible verses:

- 5 Old Testament. (Josh 1:5, Psa 23:6, Psa 108:5, 119:105, Prov 3:17)

- 11 New Testament. (Mat 19:19, John 1:1, 11:35, 19:28, Rom 3:23, 1Cor 13:8, 13:13, 2Cor 12:9, Eph 2:8, Philp 4:13, Rev 1:8)

The introduction to the book, in a disclaimer, outlined that it contained “Aramaic Words, Aramaic Phrases,” and “Aramaic Verses” in three different scripts: Paleo-Hebrew, Square (“Hebrew”) script and Syriac.

In reference to how the scripts are used, it claims that “different Aramaic dialects are used, without adherence to historical accuracy in the choice of script.”

It also mentioned that:

“The author and publisher specifically disclaim any responsibility for any liability, loss or risk, personal or otherwise, which in incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly of the use and application of any of the contents of this e-book. It is the buyer’s sole responsibility to verify that the translation meets his or her requirements.”

Which I personally found a little odd (more on that later); however, after getting past it, I took the time to let some initial observations sink in.

Initial Observations

Unlike what the introduction claimed, there were no “Aramaic phrases” (unless one argues “l’almin” or “forever” as a phrase, which then raises the count to 1). However, this may simply be advertising, or a display of intent for future revisions (which I hope is the case).

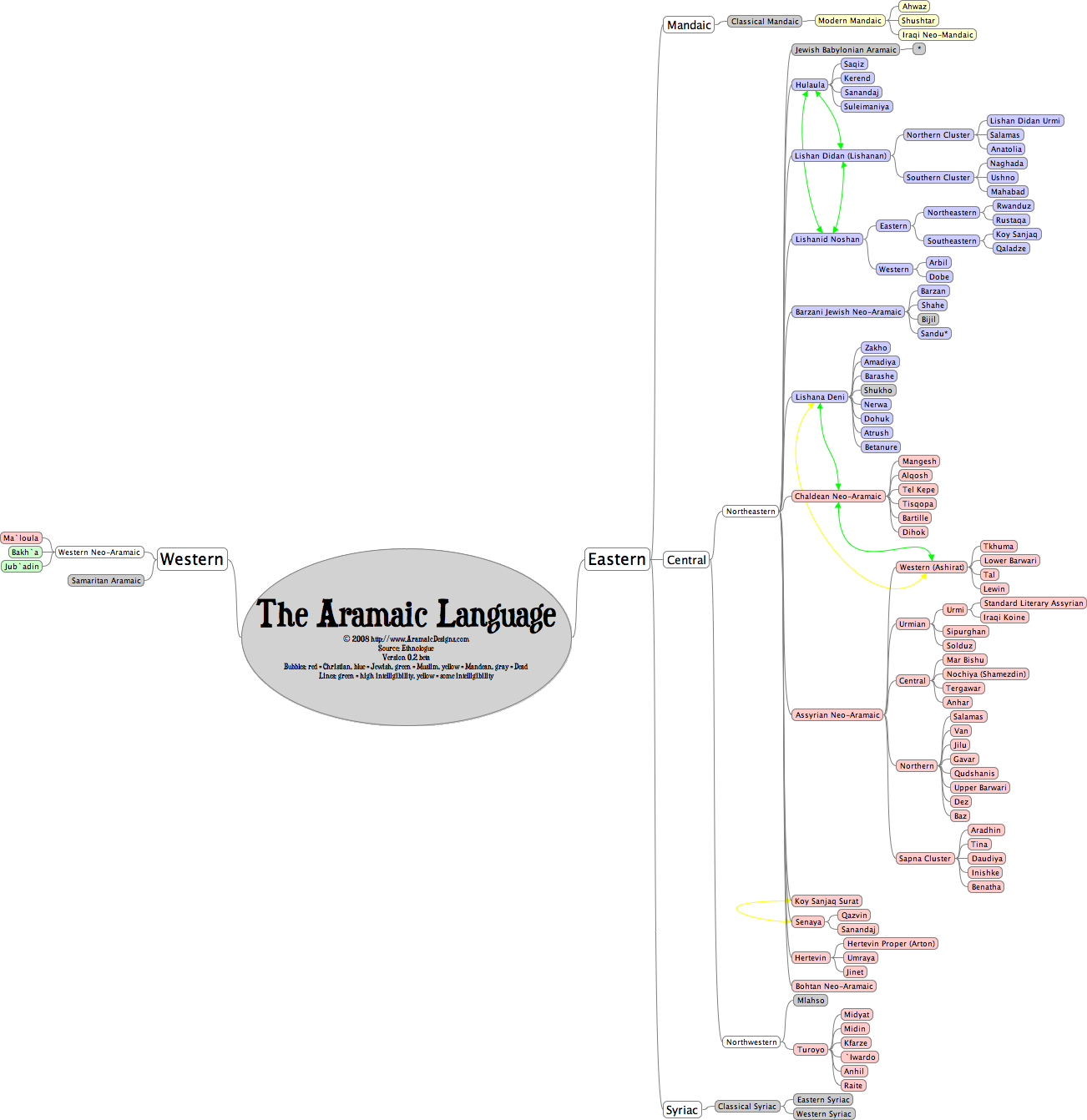

What really got me in the intro, however, was with all of the variation between Aramaic languages, saying “Different Aramaic dialects are used, without adherence to historical accuracy in the choice of script” would be like saying “Different Romance languages from Latin to Medieval French, Modern Italian and Catalan are used. It’s your job to figure out which one is which.”

Except that what makes up the mixture was not mentioned. There are hundreds of Aramaic dialects, most of which are mutually unintelligible.

I found this especially ironic because in the articles and advertisements pointing individuals to the eBook online extolled its accuracy, where the disclaimer immediately admits that it is not accurate to historical standards.

In my professional opinion, without any dialect information, this would leave an individual who is not familiar with the language with no context to go by to make an informed decision.

There were a large number of designs, from spirals, to tear drops, hearts, triangles, circles, and wavy lines and even a butterfly (which was kinda neat), every design (sans the Bible Verses, of course) simply repeated the same word. The repetition sometimes bridged on 10-12 times in varying sizes.

Where most of the text was preserved in vector, on every other page, some of the designs were saved as low-resolution images. While inspirational, they are simply not high-quality enough to take to a tattoo parlor for stenciling without some additional difficulty.

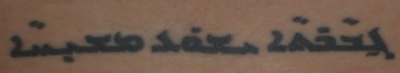

Some of the other designs, specifically the “circlets” and some of the spirals warp the text so much that if they were to be tattooed, within a few years they would likely be illegible, due to bleed (depending on the ink used and size of the tattoo).

Furthermore, some of the Syriac texts’ baselines aren’t lined up properly, so letters aren’t properly connected, leaving such corrections up to the judgment of the tattoo artist inking the design.

Finally (which is what I think is very important to note) there is no contact information anywhere in the document: No address, no phone number, no fax. The name of the translator is also missing. No sources were cited anywhere in the document either to help the customer figure out things like (for example) which dialects they were working with.

The Accuracy of the Content

Now, all of the technical observations aside, reading over all of the content and checking each unit off, I found the following pertaining to the accuracy of the actual Aramaic employed:

Out of the 39 words 18 of them (roughly half) had some problem or issue, outlined below. The following columns depict the word in question, which scripts it is (out of those that it was provided in) historically attested in, as well as any particular notes about the word, itself as it appeared in the Tattoo eBook:

| Word | Old Aramaic Script | “Hebrew” Script | Syriac Script | Notes |

| “Love” | not attested |

attested* | common | In Old Aramaic and in most dialects written in Hebrew script, this could be confused for “sin” or “debt” as it is a homograph. Depending on context, a different inflection of the root chosen would have been more appropriate, or a proper, documented noun-form from the root rḥm instead. |

| “Truth” | not attested | rare | common | |

| “Health” | not attested | not attested | common | |

| “Joy” | not attested | not attested | common | The Lexicon Syriacum (2nd ed) defines this form primarily as “suavity, jocundity.” Ḥadutha would have been more appropriate for all scripts. |

| “Freedom” | not attested | not attested | common | This is a Syriac and Christian Palestinian Aramaic (“CPA”) spelling. All other dialects use a yod instead of alef. |

| “Flame” | not attested | not attested | common | This is another Syriac and CPA spelling and a specialized term. Nura or “Fire” would have worked better here for all scripts. |

| “Life” | not attested | rare | rare | This is a rare and unusual form for ‘life’. Ḥaye is best in Syriac, where ḥaya or ḥayyin is best for the other two. |

| “Gem” | not attested | rare | common* | This word generally means “pearl” not “gem.” (Lec. Syr.) |

| “Light” | common* | common* | common | In Old Aramaic and Hebrew Scripts it’s usually nhora. |

| “Paradise” | not attested | not attested | rare | |

| “Dance” | not attested* | not attested* | common | As a noun it is only attested in Syriac, but it is possible that this could appear in other forms. |

| “Beauty” | not attested but certainly possible |

common* | common* | Can be confused for “Shofar.” A less-ambiguous alternative could have been shapira/tha (“beautiful”) or perhaps even ziwa (“splendor / beauty”). |

| “Heaven” | rare* | common | common | In Old Aramaic, was much more common as shmayin. |

| “Dawn / Twilight” | not attested | not attested | very rare | A vastly more common form would be nogha for Old Aramaic and Hebrew and nugha for Syriac. |

| “Sunrise” | not attested | not attested | common | A Syriac form that means “shining” more than “sunrise.” Again nogha / nugha would have been a better choice. |

| “Resur-rection” | not attested | not attested | common | |

| “Grace / Goodness” | common | common | common | Simple typesetting error; the font for Old Aramaic is not rendered properly. |

| “Music” | ? | ? | ? | I could not find this noun form attested anywhere, although I could imagine it being used (zmara with -utha suffixed to denote an expanded domain, like the difference between malka “king” and malkutha “kingdom”); however, it would have been better to simply use zmara (“song”) which is very commonly attested. |

The Bible verses from the Old Testament were taken from various Targums (Targum Johnathan, Targum Psalms, Targum Proverbs, etc.) and as such some of those verses contained features that would be inappropriate to render in Syriac Script.

The Bible verses from the New Testament were taken verbatim from the Syriac Peshitta, and as expected some of them contained features that would be inappropriate to render in Hebrew or Old Aramaic Script.

All in all, the actual text was copy and paste without error from their source documents (all of which are freely available on the Internet), so if one were to keep to Hebrew script for the Old Testament verses and Syriac Script for the New Testament verses, there would be little to no chance of error. This certainly does, however, reduce the number of “usable” scripts per verse.

Closing Thoughts

With everything said, my hopes in posting this article were twofold:

1) My primary goal is to ensure that individuals who have purchased this eBook do not tattoo upon them anything that is not what they expect. As my blog here has documented over the past 3-4 years, mistakes when it comes to Aramaic tattoos are rampant, and most of that, in my professional opinion, is due to individuals not researching well enough to understand the depth of the language.

2) At this point, I sincerely hope in all good faith that the owner of My-Aramaic-Tattoo.com takes this opportunity to edit their mistakes and make their product better and more suitable towards its intended purpose.

The issue of scripts and dialects with Aramaic is a very serious one as Aramaic is not one language, but a family of closely-related languages, many of which are mutually unintelligible.

To illustrate typesetting Aramaic characters in a script inappropriate to their dialect, I feel that a more lengthy example is in order. Where both the language I am conveying this paragraph in and the script I am using are both indisputably English, would this pass as acceptable for publication in a newspaper? Perhaps if it was some commentary about anachronism it would be a fitting art piece, but beyond that it is distinctly odd.

If you were wondering what was going on, the above was Modern English, typeset in Old English letters and spelling. Writing Syriac in Old Aramaic or vice-versa would seem equally as odd.

Before obtaining a tattoo in any language in which you are not well versed, always double-check. With tattoos, it’s a matter of “measure twice, bleed once.”

Finally, if you aren’t sure about some Aramaic you’re thinking about tattooing on your body, email me first. I have been double-checking tattoo translations pro bono for years and am always willing to help.

Peace,

-Steve